News release

From:

State of the Climate in 2018 shows accelerating climate change impacts

The physical signs and socio-economic impacts of climate change are accelerating as record greenhouse gas concentrations drive global temperatures towards increasingly dangerous levels, according to a new report from the World Meteorological Organization.

The WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2018, its 25th anniversary edition, highlights record sea level rise, as well as exceptionally high land and ocean temperatures over the past four years. This warming trend has lasted since the start of this century and is expected to continue.

“Since the Statement was first published, climate science has achieved an unprecedented degree of robustness, providing authoritative evidence of global temperature increase and associated features such as accelerating sea level rise, shrinking sea ice, glacier retreat and extreme events such as heat waves,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

These key climate change indicators are becoming more pronounced. Carbon dioxide levels, which were at 357.0 parts per million when the statement was first published in 1993, keep rising – to 405.5 parts per million in 2017. For 2018 and 2019, greenhouse gas concentrations are expected to increase further.

The WMO climate statement includes input from national meteorological and hydrological services, an extensive community of scientific experts, and United Nations agencies. It details climate related risks and impacts on human health and welfare, migration and displacement, food security, the environment and ocean and land-based ecosystems. It also catalogues extreme weather around the world.

“Extreme weather has continued in the early 2019, most recently with Tropical Cyclone Idai, which caused devastating floods and tragic loss of life in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi. It may turn out to be one of the deadliest weather-related disasters to hit the southern hemisphere,” said Mr Taalas.

“Idai made landfall over the city of Beira: a rapidly growing, low-lying city on a coastline vulnerable to storm surges and already facing the consequences of sea level rise. Idai’s victims personify why we need the global agenda on sustainable development, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction,” said Mr Taalas.

The start of this year has also seen warm record daily winter temperatures in Europe, unusual cold in North America and searing heatwaves in Australia. Arctic and Antarctic ice extent is yet again tracking near record lows.

According to WMO’s latest Global Seasonal Climate Update (March to May), above average sea surface temperatures – partly because of a weak strength El Niño in the Pacific – is expected to lead to above-normal land temperature, particularly in tropical latitudes.

Climate Action Summit

The WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate report will be formally launched at a joint press conference with UN Secretary General António Guterres, UN General Assembly President María Fernanda Espinosa Garcés and WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas at United Nations headquarters in New York. It coincides with a high-level meeting on Climate and Sustainable Development for All.

“The data released in this report give cause for great concern. The past four years were the warmest on record, with the global average surface temperature in 2018 approximately 1°C above the pre-industrial baseline,” Mr Guterres wrote in the report. “There is no longer any time for delay,” said Mr Guterres, who will convene a Climate Action Summit at Heads of State level on 23rd September 2019. The State of the Climate report will be one of WMO’s contributions to the Summit. Mr Taalas has been appointed Chair to the Summit’s Science Advisory Group.

“It is one of my priorities as the President of the General Assembly to highlight the impacts of climate change on achieving the sustainable development goals and the need for a holistic understanding of the socio-economic consequences of increasingly intense extreme weather on countries around the world. This current WMO report will make an important contribution to our combined International action to focus attention on this problem,’’ said Ms Espinosa Garcés.

Highlights of the WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2018

Climate impacts (based on input from UN partner agencies)

Hazards: In 2018, most of the natural hazards which affected nearly 62 million people were associated with extreme weather and climate events. Floods continued to affect the largest number of people, more than 35 million, according to an analysis of 281 events recorded by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) and the UN International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Hurricane Florence and Michael were two of fourteen “billion dollar disasters” in 2018 in the United States of America (USA). They triggered around US$49 billion in damages and over 100 deaths. Super typhoon Mangkhut affected more than 2.4 million people and killed at least 134 people, mainly in the Philippines.

More than 1600 death were associated with intense heat waves and wildfires in Europe, Japan and USA, where they were associated with record economic damages of nearly US$24 billion in USA. The Indian state of Kerala suffered the heaviest rainfall and worst flooding in nearly a century.

Food security: Exposure of the agriculture sector to climate extremes is threatening to reverse gains made in ending malnutrition. New evidence shows a continuing rise in world hunger after a prolonged decline, according to data compiled by United Nations agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Food Programme. In 2017, the number of undernourished people was estimated to have increased to 821 million, partly due to severe droughts associated with the strong El Niño of 2015–2016.

Displacement: Out of the 17.7 million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) tracked by the International Organization for Migration, over 2 million people were displaced due to disasters linked to weather and climate events as of September 2018. Drought, floods and storms (including hurricanes and cyclones) are the events that have led to the most disaster-induced displacement in 2018. In all cases, the displaced populations have protection needs and vulnerabilities.

According to UNHCR’s Protection and Return Monitoring Network, some 883 000 new internal displacements were recorded between January and December 2018, of which 32% were associated with flooding and 29% with drought. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees were affected by secondary displacement due to extreme events, heavy rain, flooding and landslides

Heat, Air Quality and Health: There are many interconnections between climate and air quality, which are being exacerbated by climate change. Between 2000 and 2016, the number of people exposed to heatwaves was estimated to have increased by around 125 million persons, as the average length of individual heatwaves was 0.37 days longer, compared to the period between 1986 and 2008, according to the World Health Organization. These trends raise alarm bells for the public health community as extreme temperature events are expected to be further increasing in their intensity, frequency and duration.

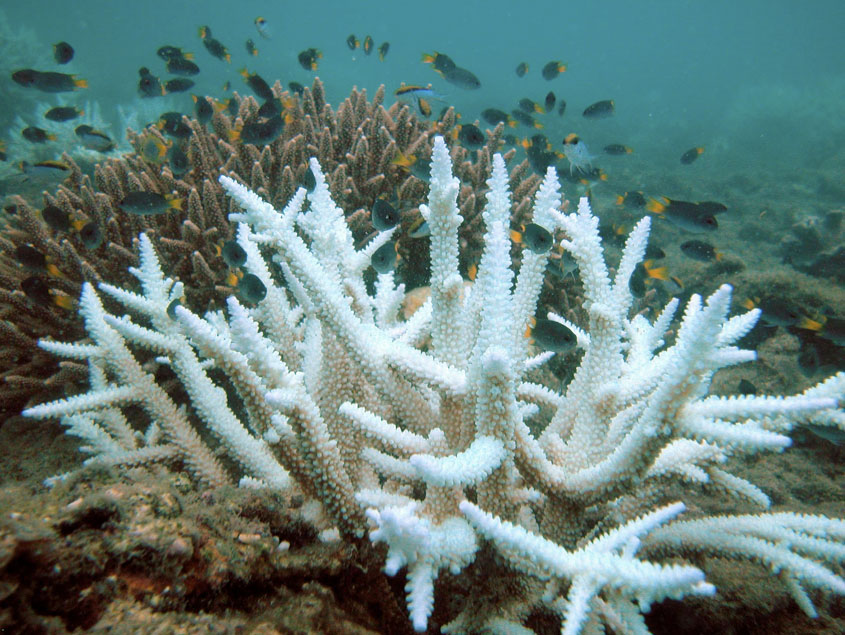

Environmental Impacts include coral bleaching and reduced levels of oxygen in the oceans. Others include loss of “Blue Carbon” associated with coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrasses and salt marshes; and ecosystems across a range of landscapes. Global warming is expected to contribute to the observed decrease of oxygen in the open and coastal oceans, including estuaries and semi-enclosed seas. Since the middle of the last century, there has been an estimated 1-2 % decrease in the global ocean oxygen inventory, according to UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO-IOC).

Climate change has emerged as a significant threat to peatland ecosystems, because it exacerbates the effects of drainage and increases fire risk, according to UN-Environment. Peatlands are important to human societies around the world. They contribute significantly to climate change mitigation and adaptation through carbon sequestration and storage, biodiversity conservation, water regime and quality regulation, and the provision of other ecosystem services that support livelihoods.

Climate indicators

Ocean heat: 2018 saw new records for ocean heat content in the upper 700 metres (data record started in from 1955) and upper 2000m (data record started in 2005), topping the previous record set in 2017. More than 90% of the energy trapped by greenhouse gases goes into the oceans and ocean heat content provides a direct measure of this energy accumulation in the upper layers of the ocean.

Sea level: Sea level continues to rise at an accelerated rate. Global Mean Sea Level (GMSL) for 2018 was around 3.7 millimetres higher than in 2017 and the highest on record. Over the period January 1993 to December 2018, the average rate of rise is 3.15 ± 0.3 mm yr-1 while the estimated acceleration is 0.1 mm yr-2. Increasing ice mass loss from the ice sheets is the main cause of the GMSL acceleration as revealed by satellite altimetry, according to the World Climate Research Programme global sea level budget group, 2018.

Ocean acidification: In the past decade, the oceans absorbed around 30% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Absorbed CO2 reacts with seawater and changes the pH of the ocean. This process is known as ocean acidification, which can affect the ability of marine organisms such as molluscs and reef-building corals, to build and maintain shells and skeletal material. Observations in the open-ocean over the last 30 years have shown a clear trend of decreasing pH. In line with previous reports and projections, ocean acidification is ongoing and the global pH levels continue to decrease, according to UNESCO-IOC.

Sea ice: Arctic sea-ice extent was well below average throughout 2018 and was at record-low levels for the first two months of the year. The annual maximum occurred in mid-March and was the third lowest March extent in the 1979-2018 satellite record. The September monthly sea ice extent was the sixth smallest September extent on record. The 12 smallest September extents have all occurred since 2007. At the end of 2018, the daily ice extent was near record low levels.

The Antarctic sea ice extent reached its annual maximum in late-September and early-October. After the maximum extent in early spring, Antarctic sea ice declined at a rapid rate with the monthly extents ranking among the five smallest for each month through the end of 2018.

The Greenland ice sheet has been losing ice mass nearly every year over the past two decades. The surface mass budget (SMB) saw an increase due to above-average snowfall, particularly in eastern Greenland, and a near-average melt season. This led to a gain in overall SMB, but had little impact on the trend over the past two decades with the Greenland ice sheet having lost approximately 3,600 gigatons of ice mass since 2002. A recent study also examined ice cores taken from Greenland, which captured melting events back to the mid 1500s. The study determined that the recent level of melt events across the Greenland ice sheet have not occurred in at least the past 500 years.

Glacier Retreat: The World Glacier Monitoring Service monitors glacier mass balance using a set of global reference glaciers with more than 30 years of observations between 1950 and 2018. They cover 19 mountain regions. Preliminary results for 2018, based on a subset of glaciers, indicate that the hydrological year 2017/18 was the 31st consecutive year of negative mass balance.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Helen Cleugh is Director of CSIRO's Climate Science Centre

The findings of the latest WMO State of the Climate are consistent with the key messages from Australia’s 2018 State of the Climate, published by CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology, including that greenhouse gas concentrations have reached levels not seen in over 2 million years and at Australia’s Cape Grim station have already exceeded 500 ppm CO2 equivalent; ongoing ocean warming over the full ocean depth and rising sea levels; and increased day and night-time temperatures across all seasons and all of Australia.

Australia is already seeing the impacts of these changes in our climate including increased frequency and intensity of marine and land-based heatwaves and a long-term increase in extreme fire weather. Over the coming decades Australia is likely to experience further warming, more hot days and fewer extremely cool days, and ongoing ocean warming and sea level rise. Climate change impacts will therefore continue to be experienced into the future.

Dr Liz Hanna is Chair of the Environmental Health Working Group at the World Federation of Public Health Associations, and an Honorary Senior Fellow at the Climate Change Institute, The Australian National University

The key word in this report is 'accelerating'. Impacts are accelerating as global CO2 emissions are again accelerating, they rose 2.7 per cent last year. Rather than offering intelligent respite in this mad trajectory to species suicide, Australia is only making it worse. Excluding the unreliable land use data, Australia’s emissions hit an all-time high last year.

Acceleration of warming, of heat extremes, fires drought, damaging storms and sea level rise sends shivers up the spines of the health sector. These rising climate tragedies spell disaster for human lives, human livelihoods, and our collective health and happiness crumble. The health sector is left to pick up the pieces and try to restore health.

As individuals, humans have a strong survival instinct, it appears that collectively we do not.

Rich countries are not immune to the damage and misery global warming is starting to deliver. While we watch Cyclone Idai devastate three nations in Africa, Australians are still reeling from two synchronous cyclones across the north, swathes of flood damage across drought-stricken Queensland, with heat fires and droughts sending the southern half of Australia into despair. And all this is accelerating!

Peter Newman is the Professor of Sustainability at Curtin University

Australia has had its hottest year on record, by far, with huge swings in rainfall, what else do we need in Australia to motivate us to do more about demonstrating leadership on reducing greenhouse gases?

Professor Kadambot Siddique AM is Hackett Professor of Agriculture Chair and Director of The UWA Institute of Agriculture, The University of Western Australia

A major challenge of our time is to produce sufficient nutrient‐rich food for the ever-growing human population with limited land resources at time when climate change is occurring.

Globally, farming contributes around 8–15 per cent of the total anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas (GHS) emissions. More than 60 per cent of the emissions associated with a food commodity come from farm‐gate raw materials; as such, grain producers, agri‐food industries, policy‐makers, and consumers share the responsibility of securing the food supply while mitigating the environmental footprint.

Farming is a socioeconomic‐ and technology-driven ecosystem with the complexity of simultaneously implementing technologies for quality food production, ensuring positive economic and environmental outcomes, maintaining and improving soil quality and health, and endeavouring to uphold societal values.

Adopting ‘systems integration’ of proven farming strategies in a production ‘package’ can lead to the ‘decoupling’ of increasing land productivity and reducing GHG footprints.

Specific cropping strategies that can be integrated into farming systems include (i) diversifying crop rotations to break pest cycles, and increase the use of residual soil water and nutrients; (ii) optimising fertilisation and improving fertiliser‐Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) in crop production; (iii) incorporating pulse crops into rotations to enhance biological N2‐fixation and reduce fertiliser use; (iv) enhancing soil carbon sequestration to partially offset GHG emissions from inputs; (v) adopting low soil–disturbance practices, where possible, to increase soil organic carbon; and (vi) intensifying crop rotations with reduced summer‐fallowing frequency to increase carbon inputs to the system. Integrating these proven practices in a system, with the support of relevant policies and consumer intervention, would enhance the synergy of individual components, leading to increased system productivity and profitability, while reducing the end–product footprint and environmental impacts, and enhancing societal values.

Ian Lowe is Emeritus professor of science, technology and society at Griffith University, Qld and former President of the Australian Conservation Foundation.

This latest statement from the World Meteorological Organization is truly alarming. It documents increasing average temperatures, more extreme weather-related events such as heatwaves, cyclones and fires, accelerating sea level rise, shrinking sea ice and retreat of glaciers. Greenland has lost about 3600 cubic kilometres of ice since 2002. As the UN Secretary-General says, the data in the report 'give cause for great concern'. 'There is no longer any time for delay', he said, calling for concerted international action.

Our national government is still dithering, as if responding to climate change is an optional extra to be implemented only if it doesn’t slow economic growth. There is clear evidence that it is technically possible, as well as economically prudent, to move rapidly to de-carbonise our electricity supply. A recent opinion poll in South Australia showed an overwhelming majority of voters recognise the urgency of the situation and support moving to 100 per cent renewables by 2030.

We also need, as a matter of equal urgency, to tackle the problem of increasing greenhouse gas emissions from transport. Governments are still investing billions of public funds in dinosaur road schemes which will worsen the problem. That money should be invested in providing world-class public transport systems for our cities and high-speed inter-urban rail.

Professor John Quiggin is a Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland

Following the depressing news from the International Energy Agency that global CO2 emissions rose to a record high in 2018, the WMO report confirms that severe impacts of climate change are already being felt. This scientific analysis only confirms what is evident to anyone who examines the evidence with an open mind: the global climate is changing in ways that are unprecedented in human experience. Sadly, many of our leaders do not have an open mind. Rather, they are committed to denying the findings of climate science at any cost, in order to defend sectional economic interests and backward-looking identity politics. Australia in particular needs urgent action to achieve substantial reductions in emissions over the next decade.

Dr Jim Salinger Honorary Research Associate University of Auckland

The 25th Anniversary issue [of the WMO report] shows hastening climate warming globally. This was true for the New Zealand region, a combined land and marine area of 4 million sq. km (the size of the Indian subcontinent), with the warmest year on 150 years of land and sea records. It is very alarming that the carbon dioxide levels reaching a highest 406 ppm – up from 280 ppm in the 19th century, and methane jumping unexpectedly by 25 ppb to a record 1850 ppb by 2017. The extra 3.7 mm of sea level rise will be very significant for the coast of Australia, and especially New Zealand with its many seaside urban areas and long coasts. The record warm summer ending in February 2018 produced the largest ice loss on the Southern Alps glaciers since the regular end of summer snowline surveys started 42 years ago. As well Queensland Groper occurred in the Bay of Islands, Northland, 3,000 km out of range, Snapper in Milford Sound in Fiordland, with massive mortality in the aquaculture fisheries of the Marlborough Sounds. These are a harbinger of climate in the latter part of the 20th century if we do not take action to reduce emissions from combustion of fossil fuels and production of greenhouse gases from other sources such as waste and agriculture immediately.

Professor Samantha Hepburn is a Professor in Energy Law at Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This report makes it very clear that the impacts of climate change are accelerating. We know that if the current trajectory for greenhouse gas concentrations continues, temperatures may increase by 3 - 5 degrees celsius compared to pre-industrial levels by the end of the century and we have already reached 1 degree celsius.

The 20 warmest years on record have been in the past 22 years, 2018 was the fourth warmest year on record, ocean heat content is at a record high, global mean sea levels continue to rise, Arctic and Antarctic ice content have been severely diminished, extreme weather patterns have impacted life in every continent and imperil sustainable practices and global emission reduction targets have not been met.

Clearly, the soft law processes of international law have not been effective in addressing this profound threat to humanity. Domestic regulatory and policy frameworks across the world must take immediate, strong and direct action to stem the growth of global carbon emissions.

In addition to pricing carbon and accelerating the trajectory of renewable energy, there are many multi-dimensional options that may work. These include climate accession agreements, bottom-up approaches, green clubs and strategies grounded in behavioural science.

Responding to climate change is fundamentally a legacy decision. It connects to our global intergenerational responsibilities. Even if we do manage to reduce emissions by 2020, the global average temperature will rise for many decades and sea levels will continue to rise. The benefits of near-term emissions will therefore not be apparent for decades. But this is our moral imperative.

In the words of Obama, 'Someday our children and our children's children will look us in the eye and ask us did we do all we could, when we had the chance, to leave a cleaner, safer world? And I want to be able to say yes.

Associate Professor Paul Read is at Charles Sturt University and Director of the Future Emergency Resilience Network (FERN)

The latest report on the state of the climate from the World Meteorological Organization is in its 25th year. The science has never been more certain and the impact of climate change is in the news daily, Mozambique and Zimbabwe being the latest casualties to its growing and tragic consequences. The developed world, in particular countries like Australia, are more blameworthy than others for 25 years of political inaction.

The issue of climate change in Australia has toppled Australian governments one by one since Professor Garnaut tried to introduce a program that would have Australia on track to meet its global obligations; sea levels are definitely rising, deaths from climate change are rising, oceans are becoming acidic, and still Australia fiddles like Nero as Rome burns.

The Australia-wide strike of school children reminds me of the Children's Crusade of the Middle Ages. After 25 years of inaction we need our children to remind us what's important and sadly their initiative becomes yet another example of an intergenerational social contract shattered - between the older 'haves' and the younger 'have nots'.

Associate Professor Linda Selvey is in the School of Public Health at the University of Queensland.

The WMO report highlights the unprecedented climate extremes around the world in 2018, as well as the continued growth in carbon emissions and ocean acidification. Australia is not immune and in Australia we experienced unprecedented heat waves, fires, floods, drought and storms. Heat waves are deadly and also affect peoples’ general health and wellbeing. Floods, fires and storms injure and kill people and also have long-lasting impacts on peoples’ mental and physical health. Our food security is also under threat by severe droughts and flooding. While most of us in Australia have enough food to eat, droughts and floods can limit the affordability healthy food, particularly fresh fruit and vegetables. This has major implications for public health

Professor Pete Strutton is from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes

The WMO State of the Climate 2018 report reiterates the scientific consensus around climate change, and importantly highlights the economic and societal impacts. The report documents continued increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, land and ocean temperatures, sea level rise and ocean acidity, as well as continuing decreases in glacier mass and low ice extent in the Arctic and Antarctic. All of the major indicators are confirming the impacts of climate change.

Importantly, the report makes links between climate change and societal issues such as human displacement and nutrition. For example, in 2017 the number of undernourished people increased after a prolonged decline, due to droughts associated with the strong 2015-16 El Niño.

For Australia, the most pertinent aspects of the report are the indicators for increasing land and ocean temperatures (including heat waves in both and the links to drought) and sea level rise, given the coastal concentration of the Australian population

Australia; International; VIC; QLD; WA; TAS; ACT

Australia; International; VIC; QLD; WA; TAS; ACT