Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Professor Wasim Saman is an Emeritus Professor of Sustainable Energy Engineering at the University of South Australia

The government appear to be hedging its bets by declaring such a wide range rather than a single defined target. Realistically, the upper figure may bring us closer to a more manageable global warming in the midrange of the recently published climate change risks report. It is hard to see how we can reach net zero by 2050 if we land at the lower figure by 2030. The anticipated time, effort and cost of the last third of our emissions associated with transport, industry and agriculture will be much harder to mitigate than the middle third.

Professor Stuart White AM is Director of the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology, Sydney

"While the target range is at the lower end of what the science suggests, the important thing is that we must put in the plan to meet the higher end of that range.

Australia is well placed to meet the higher end of this range and even beyond, but we need to accelerate efforts.

The domestic energy transition is well underway, especially in the electricity sector, with the rollout of renewables and battery storage, but needs to increase to meet even 2030 targets.

There needs to be a renewed focus on consumer energy resources, also known as distributed energy resources, which are quicker and alleviate the pressure on new large-scale projects that are moving more slowly due to social licence issues.

We need to lift our game on decarbonising industry, transport, and on agriculture and land use.

All of this requires increased investment - so we need to do more to mobilise climate finance."

Flavio Menezes is a Professor of Economics and Director of the Australian Institute for Business and Economics at The University of Queensland

"The 62-70% target is a welcome commitment to action. It sends a strong signal to businesses, individuals, and investors that Australia is serious about addressing climate change. This signalling is crucial as it focuses our minds on the massive reallocation of resources needed to achieve these targets and the mechanisms required. Businesses must now demonstrate their commitment by shifting to green production and rethinking sourcing and delivery methods. It is also essential for individuals to understand what is required of them in terms of changing consumption, travel, energy, and water usage habits. Importantly, to avoid catastrophic outcomes, we need to view the target as a minimum goal and strive to reach 70%."

Professor Rodney Keenan is from the School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences at the University of Melbourne

"The Prime Minister has announced an ambitious, but feasible, emissions reduction target that reflects the challenges associated with energy transition and uptake of new transport technologies. Land based activities are a significant contributor to the new target, with reforestation needing to sequester over 100 Mt of CO2-e per year by 2050. This will require a massive effort to reforest 10 million hectares of land over the next 25 years. Current policies are delivering about 20,000 ha per year, or 5% of what is needed.

A step change in policy is needed, working with local governments, farmers, Indigenous communities, NGOs, private developers and other land owners to increase the rate of reforestation. We need flexible, farmer-led approaches and look beyond grants to invest in forestry capacity, seedling nurseries, site preparation and tree planting and management crews.

With strong political commitment at all levels, and well-designed incentives, we can drive private sector investment in trees across Australia to increase carbon stocks, farm productivity, timber supply, biodiversity and many other environmental and social benefits."

Professor Matthew Harrison FTSE is a farming systems scientist at the University of Tasmania

"Climate change is one of the greatest threats to humanity in the 21st century: if we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions, global warming will invoke more frequent extreme events – storms, rainfall, heatwaves, fire – to cataclysmic effect.

It is paramount that Australia, and every nation across the planet, reduces their GHG emissions now and in future. But because there is a tight coupling between productivity and GHG emissions, the reduction in GHG must be gradual to avoid impacting on food security or prosperity.

Interim targets, including the 62-70% GHG reduction by 2035 released today, are essential for any net-zero aspiration, because they create milestones that tell us if we are on track on not. Part of the 2035 target is the agriculture and land sector plan, which creates opportunities and threats to farm businesses.

On the one hand, land managers have the opportunity to innovate, invest in negative emissions technologies, improve carbon storage and protect existing biodiversity. On the other hand, our agricultural exports will eventually be taxed by overseas purchasers if we don’t put low-emissions plans in place.

The opportunity for Australian producers is to use carbon storage in soils and vegetation to their advantage, and proactively document their progress towards lower emissions through short and long-term farm management planning."

Associate Professor John Tibby is from the Department of Geography, Environment and Population in the the Environment Institute at The University of Adelaide

"Reducing emissions is the only guarantee the world has to avoid dangerous climate change. We can’t “wait and see” since it will mean crossing dangerous thresholds (like losing the Greenland ice cap). Australia is in the top 20 worst emitters of greenhouse gases, yet the nation and its precious environment is highly vulnerable to climate change. Without large scale pollution abatement we risk losing the environments and way of life that Australians hold so dear. Events like the horrendous algal bloom off South Australia’s coast will become commonplace without pollution reductions. This announcement is a substantial step in the right direction for Australia to meet its legal and ethical obligations. Committing to these new targets highlights to the public the risk of climate change and will greatly strengthen Australia’s diplomatic credibility in arguing for other countries to reduce their emissions."

Dr Greg Dingle is a Senior Lecturer in Sports Management at La Trobe University

“The announcement by the Australian Government of the 2035 Climate Emissions reduction target marks a turning point for the sport sector

In the context of Australia’s commitment to the 2015 Paris climate agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 C. above long-term average temperatures, 2035 Climate Emissions reduction target suggests that the transition away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy will affect all sectors of the Australian economy including the sport sector.

The decision to cut Australia’s emissions by between 62 to 70 per cent by 2035 signals to all sectors, including sport, that the fossil fuel era is inexorably drawing to a close. For sport organizations, this poses questions and presents both challenges and opportunities.”

- How will sport organizations approach meeting Australia’s emissions by between 62 to 70 per cent by 2035?

“The target signals that Australia is committing to a long-term process of decarbonizing our economy. For sport organizations, this suggests challenges lie ahead. First, it’s difficult to reduce emissions that haven’t been measured so an initial task for sport is to quantify emissions. Given the range of tools for calculating emissions that are already available, this is reasonably straightforward. Second, assuming sport organizations can quantify their emissions, how do we report these emissions to government or to our industry partners?

Most importantly, the task of decarbonising sport activities is now a clear and present challenge. Some tasks will be relatively straightforward, however, other decarbonising tasks will inevitably be more challenging, for example, those faced by board and management teams with national and international sport competitions that rely on carbon-intensive transport systems.

Despite the questions and challenges, opportunities for the sport sector can be found within the 2035 emissions target. Sport organizations with sponsorships involving fossil fuel companies may now find it easier to find corporate partners in the renewables sector.

Secondly, the new context of economy-wide decarbonisation presents opportunities to reduce input costs – it is now likely to be easier for sports organisations to replace inputs from electricity or gas with lower cost renewable inputs.

The sport sector, under Australia’s mandatory climate risk disclosure regime, is being challenged to think about the climate risks that are unfolding. Within the medium term, larger professional sport organisations with significant assets or revenues will fall within the thresholds and so will be required to disclose such risks. Together with the 2035 emissions reduction target, the climate risk disclosure regime points to a period where the sport sector is being challenged to integrate climate change into its strategic and operational thinking. Ignoring climate change is now no longer an option.”

Dr Rob Hales is an Associate Professor from Griffith Business School at Griffith University

"Australia’s latest government emissions reduction announcement today falls short of a scientific approach to target setting. The target relies on economic modelling that only accounts for the direct costs of emissions abatement policies, while ignoring the vastly more significant economic consequences of failing to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Importantly, the Treasury’s recent reports focused on sector operations and flow on effects under more modest reduction scenarios. This omission means today’s discussion of 'costs to the economy' rests on a partial and limited analysis, rather than the true cost-benefit framework required for globally responsible climate policy.

Independent modelling from the Climate Change Authority, Climate Works Centre, and major consultancies all show that cuts above 70% by 2035 are technically feasible and economically credible. In stark contrast, research from Australia’s leading institutes demonstrates that missing the Paris Agreement could cost the nation A$126–130 billion annually in GDP, with up to A$6.8 trillion in cumulative losses by 2050. Findings from the 2023 Intergenerational Report indicate that failing to limit global temperature rise to 2°C (i.e., reaching 3°C) could reduce Australia's economic output by between AUD $135 billion and $423 billion by 2063.

If the world also set the same global emissions reduction targets, there would be significant global economic impacts on jobs, exports, food production, household costs, increased disaster costs, and instability from uninsurable (devalued) housing stock. For a wealthy country like Australia to argue that climate ambition is unaffordable sends the wrong message to developing nations whose participation in responsible Paris-aligned target setting is vital for a safe climate."

Dr Tim Neal is a Scientia Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics and also the Institute for Climate Risk & Response (ICRR) at UNSW Sydney

"Australia’s economic exposure to climate change is far more complex than most models suggest. Traditionally, economists have estimated climate damages by analysing historical data linking local weather events to economic growth. However, today’s globalised economy complicates this picture.

Global supply chains currently absorb and buffer many of the economic shocks caused by extreme weather, masking the true extent of climate-related risks. As the planet warms, these supply chains are likely to be increasingly disrupted, amplifying the economic costs.

When climate risk functions in economic models are updated to account for global rather than purely local weather impacts, the projected costs of climate change rise sharply. These findings strongly support limiting global warming to 1.7 °C."

Associate Professor Christian Downie is a political scientist and policy advisor with expertise in energy politics, climate politics, and foreign affairs at the Australian National University

“While interest rates are rightly set by an independent Reserve Bank, emissions targets remain a political decision. The announcement today to cut emissions by 62 to 70 per cent by 2035, on 2005 levels, reflect that.

The target range provides the government with political flexibility, but given the damage and the economic costs to Australia from climate change, there is a strong case to aim higher. Targets are set not only to be met, they are also a signal of ambition."

Luisa Bedoya Taborda is an Environmental Lawyer, MPhil in Agriculture, Environment and related studies and PhD candidate at The University of Sydney

"Australia’s new target, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 62–70% by 2035, is a significant and necessary policy advance. While some argue this will cost jobs, slow the economy, and lower living standards, the evidence shows the opposite: investment in clean energy creates more jobs than fossil fuels, renewable industries are already driving regional growth, and energy efficiency lowers household bills.

Jobs and Skills Australia's 2023 report “The Clean Energy Generation” identified 38 critical occupations in the clean-energy economy, including trade, technical and professional roles that are projected to grow significantly and faster than the average in the broader workforce. The same report estimates that thousands of workers will be needed in generation, transmission, storage, and other supporting infrastructure if Australia is to meet net-zero emissions by mid-century.

A modelling study by the Clean Energy Council highlights that under an 82% renewables scenario by 2030, Australia would gain tens of thousands of jobs, particularly in construction and operations and maintenance of renewable energy infrastructure. The estimations are between 2026-2030, 37,700 construction “job-years” and 5,000 operations and maintenance “job-years” would be created. Even now, around 30,000 people are employed in clean energy in regional Australia, and about 40,000 jobs are expected by 2030.

Fossil fuel employment is comparatively small and declining. A report on transitions from fossil fuels shows fossil fuel-related employment is about 1% of total Australian employment, and new jobs in fossil fuel sectors have been few in recent years, while many more are being created in renewables and supporting sectors. These facts show that the notion that emissions cuts must come at the cost of jobs and prosperity is not supported by evidence. On the contrary, Australia has an opportunity to expand employment, secure economic growth in a clean economy and protect communities from worsening disasters. Communities in the Pacific Islands have already been forced to relocate, and these events are projected to become more frequent and severe."

Dr Julia Dehm is an Associate Professor and ARC DECRA Fellow in the School of Law at La Trobe University

“The International Court of Justice (ICJ) recently affirmed that all countries’ National Determined Contributions (NDCs) must reflect their highest possible ambition and that their NDC must be capable of making an adequate contribution to the global effort to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Australia’s NDC target of a 62 to 70 percent reduction is not aligned with limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius, let alone limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, which has become the scientifically based consensus target under the Paris Agreement.”

Peter Newman is the Professor of Sustainability at Curtin University

"The target of 62-70% continues the positive commitment to net zero that began with the 42% target when they began in office 5 years ago. Its most important guideline was to remain ‘achievable and investible’ in terms of the Australian economy. This is consistent with a global 2C rise in average temperature and that will be hard times for the world, but not as devastating times as if the 3C option had been unleashed, as is happening in the US.

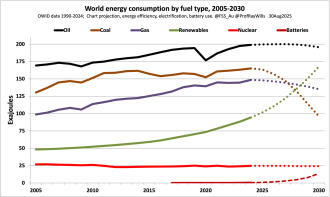

The good news is that this announcement comes on the same day that coal and oil companies were announcing how investment was on the run from new fossil fuel projects. Our recent paper in The Conversation shows why this is happening as solar energy is dramatically displacing their markets. It shows that ‘achievable and investible’ is rapidly changing due to the exponential adoption of solar, batteries and EVs, and this may mean that we will see not just 70% achieved by 2035 but a figure well beyond this. The simple global picture of the trends is shown in the figure below [available in multimedia at the bottom of the page]. This more hopeful approach is also outlined in my new book published today by Edward Elgar in London."

Professor Deanna D’Alessandro is director of the Net Zero Institute at the University of Sydney

"It’s promising to see a clear mid-term target because the risks of inaction are no longer distant, they’re here. Decarbonisation isn’t just about climate. It’s about economic security, national security, and protecting Australia’s future.

Regardless of global politics, this is a major opportunity for our country. But we must be honest: the challenges are real. What’s needed are bold, joined-up solutions, ones that work for our economy, our environment, our people, and our planet."

Associate Professor James Hopeward is the Professorial Lead in STEM at the University of South Australia

"The Australian Government’s emissions reduction modelling sits in stark contrast with the National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA) released on Monday. The NCRA depicted a climate-constrained future where we must urgently (re)learn how to live within the limits of nature.

The emissions targets are comparatively upbeat: Rather than constraints, the scenarios depict futures in which we can – simultaneously – clean up our emissions while miraculously sustaining real growth across industrial sectors and household consumption. This optimistic framing is a pervasive feature of what are termed ‘normative’ decarbonisation scenarios – that is, scenarios where we set a preferred outcome, then use sophisticated techno-economic models to force a simulation of the system to support that outcome. In this case, the preconceived outcome is continued growth, which the normative scenarios deliver through simulated assumptions of technological progress (decarbonisation of energy supply and electrification of demand).

What is poorly captured in these normative simulations is that the wholesale conversion of our energy infrastructure will itself require enormous amounts of energy – the faster we roll out wind turbines, solar panels and EVs, the more energy must be diverted from our economy, to mine and refine the materials and so on. So, if we want to phase out fossil fuels as quickly as we need to, while funnelling energy back into the green transition, our economy will inevitably face energy constraints [1].

We absolutely must push forward with the energy transition (both supply and demand), but an even more pressing need is to radically change our preferred vision of the future. Growth is, after all, a poor measure of real prosperity and wellbeing; with climate risks front of mind, now is the time to think beyond growth, and set our sights on a better goal.”

[1] Hopeward, J., Davis, R., O’Connor, S., & Akiki, P. (2025). The Global Renewable Energy and Sectoral Electrification (GREaSE) Model for Rapid Energy Transition Scenarios. Energies, 18(9), 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18092205

Dr Kat O’Mara is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Management and Sustainability at Edith Cowan University

"It was pleasing to see that the Prime Minister has acknowledged the need to increase our commitment to reducing carbon emissions, and the impact that our current approach would have on the economy and jobs. However, 62-70% is below what the science tells us that we need in order to stay below 2 degrees of warming.

As a starting place, this commitment represents a step in the right direction when it comes to working towards a net zero future by 2050, but there is still much work to be done. There is an opportunity for the business sector and states to lead the way by developing their own ambitious targets for 70% reduction by 2035. As individuals, we also have the opportunity to reduce carbon emissions by reducing our electricity and fuel consumption, which would assist in achieving the government commitment."

Dr Wesley Morgan is a research associate from the Institute for Climate Risk & Response at the University of New South Wales. He focuses on Pacific international relations and global cooperation on climate policy and security.

"Australia is bidding to host the UN climate talks with Pacific island countries, and Pacific nations are watching Australia's ambition closely. Pacific island countries are fighting for survival, and want to see all countries set a target that is in line with limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

To meet Australia’s share of global efforts to limit warming to 1.5 °C, our 2035 target should have been a cut of at least 75% on 2005 levels by 2035. This target range is short of what is required to keep communities in Australia and the Pacific safe. To maintain our place as a credible security partner for Pacific island nations, Australia will need to focus on the upper end of this target range, and will also need to signal plans to phase out fossil fuel production."

Jacqueline Peel is a Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Melbourne, and a Kathleen Fitzpatrick Australian Laureate Fellow

"This target is not likely to please anyone; progressive business called for a 75% cut, civil society for an 85% or above target, and on the right, the Coalition opposition is stuck in a diabolical debate about whether to even have Australia stick with a net zero by 2050 target.

Following hot on the heels of the National Climate Risk assessment released on Monday, which pointed to the wide ranging and severe risks and costs Australia faces from climate change, this ‘achievable’ target feels very anticlimactic.

What of the International Court of Justice's recent affirmation that the Paris Agreement’s call for parties to set targets that reflect their ‘highest possible ambition’? These are not mere words but a legal standard against which the adequacy of states’ climate action can be judged (legally). What of the desire to meet Pacific countries' call for alignment with 1.5 to ‘stay alive’ and our bid to partner with the Pacific for an ambitious COP31?

Of course, a target is only part one of any nation’s climate action story, and there is a lot to be written for the part two implementation chapter that will play a big part in judging the ambition of this new pledge.

But you can’t help wondering, if this is where we were going to land, was the journey and gestation period of the past nine months really in aid of very much? Or was this a target that had already largely been settled on prior to the Australian election in May this year?"

Tanya Fiedler is a Scientia Fellow from the Institute for Climate Risk and Response and School of Accounting, Auditing and Taxation at the University of New South Wales

"One of the potential pitfalls for business would be interpreting emissions targets as short-term compliance goals rather than the byproduct of their systemic climate resilience and transition work.

Businesses working to climate compliance, rather than competency, risk financial as well as reputational damage. This is because emissions targets are based on climate science and the laws of physics, meaning – regardless of any recent environmental, social, and governance (ESG) backlash – the climate is on the move.

The laws of physics do not break down in response to election cycles, media, trends etc. They are constant. Accordingly, and as clearly articulated in Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment released earlier this week, a rapidly changing climate will have cascading economic impacts. So, resilience and transition work, in the form of scenario analysis and risk assessment, are all part of the same piece. They are both fundamental to de-risking in a rapidly changing economy as well as climate. More than this, however, they also present strategic opportunities to re-imagine for a future that will be fundamentally different to the past.

Organisations must develop the capacity to interpret and apply scientific information and dynamic ways of planning that do not fit neatly with the types of financial models and organisational systems we are accustomed to. But without integrating the full scope of climate science, its complexities, and uncertainties, organisations risk making decisions that will increasingly undermine business resilience."

Clive Hamilton is a Professor of Public Ethics at Charles Sturt University in Canberra. He is a former member of the Climate Change Authority (2012-2017)

"After the release of the government’s do-nothing National Adaptation Plan, the message of the 2035 target is ‘It’s going to get hot and you are on your own."

Multimedia

Australia; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; WA; TAS; ACT

Australia; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; WA; TAS; ACT