Media release

From:

Big changes to Australia’s largest animals over 100,000 years reveal mammals are most vulnerable

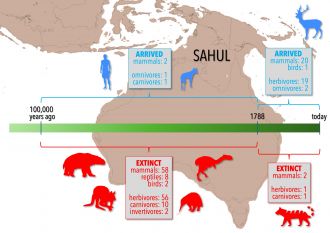

Over the past 100,000 years, Australia and New Guinea’s large animal communities have been disrupted by extinctions and invasive species, altering entire ecosystems and threatening the conservation of remaining species.

A new study led by researchers at Flinders University examined the large-bodied (more than 10 kg) animal community ‘Down Under’, comparing extinction and invasion rates of different groups of animals before versus after European invasionin the 18th Century.

Until now, there has not been a clear picture of how different types of animals — mammals, reptiles, birds — and different feeding groups were affected over this period.

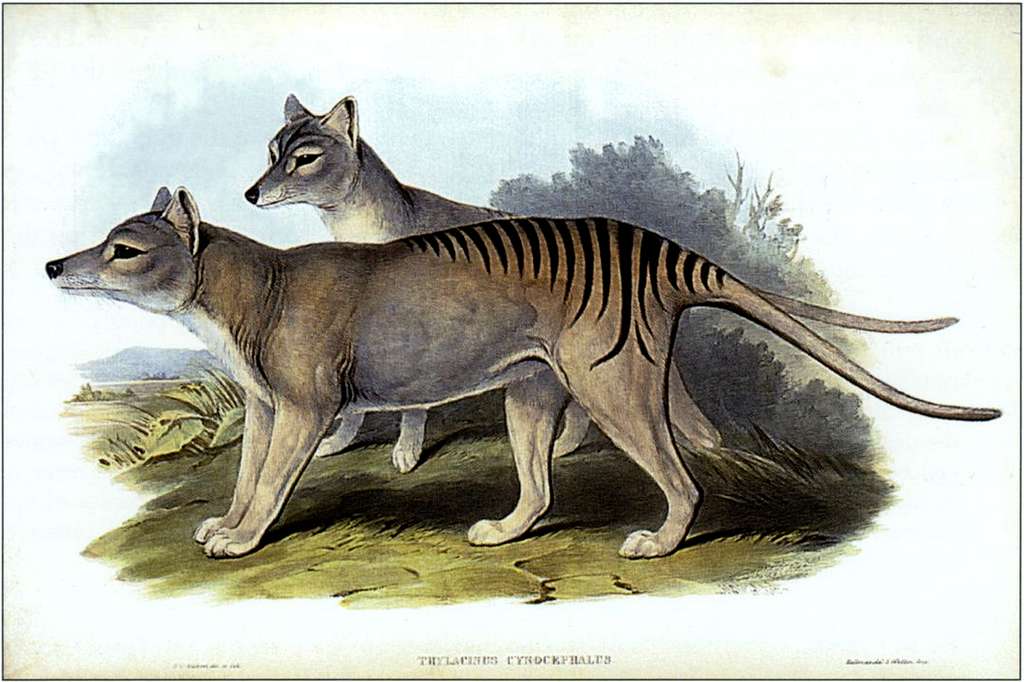

“Over the last 100,000 years, there have been huge changes in the large animal community. We lost most of the native giants tens of thousands of years ago — like Diprotodon (rhino-sized ‘wombat’ marsupial) and Megalania (6 m-long goanna) — and a swathe of new species has been introduced in the last few hundred years, threatening the survival of many of our remaining native animals,” says Dr John Llewelyn, Research Fellow in Ecological Modelling at Flinders University’s College of Science and Engineering.

Dr Llewelyn says extinctions and introductions have been selective, with mammals and herbivores most affected, while birds and reptiles have been more stable.

Understanding what makes mammals so vulnerable here — compared to other parts of the world — might be key to their conservation in the future.

“It has been suggested that our native species are vulnerable because they evolved here in isolation, separate from animals on other continents,” Dr Llewelyn adds. “However, isolation alone can’t explain why mammals specifically are so vulnerable, while reptiles and birds have been more resilient”

Not only have mammals been over-represented in the extinctions, the study found that most of the large, introduced animals are also mammals.

“This bias for introducing mammals, in combination with evolutionary isolation, could partially explain why native mammals have been so strongly affected,” says Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology Corey Bradshaw.

The study also highlighted that large mammals, reptiles, and birds differ in their diets, which could be linked to extinction vulnerability.

“Large reptiles tend to be carnivores, large birds tend to be omnivores, and large mammals tend to be herbivores,” Dr Llewelyn says, adding “omnivory — feeding from different food groups rather than specialising on one — might have helped large birds endure, while specialisation on plants could have made mammals more sensitive to natural or human-caused changes in vegetation.”

“Many unique species have been lost, and the newer additions of invasive species such as goats, deer, and pigs are having a net negative effect on native species rather than taking their ecological place” says Prof Bradshaw.

“This means it is essential to identify what ecological roles have been lost and assess how invasive species are directly and indirectly affecting native species so that targeted conservation strategies can be developed.”

Dr Llewelyn says the study reveals broad patterns in community change over time, and that the next step is to incorporate more detailed trait analyses and develop practical conservation strategies.

The research – “Trophic and taxonomic restructuring of Sahul’s large-bodied animal community since the Late Pleistocene”, by John Llewelyn, Caitlin Mudge, Frédérik Saltré, April E. Reside, Vera Weisbecker, Christopher R. Dickman, Corey J. A. Bradshaw – has been published by Quaternary Australasia.

Multimedia

Australia; NSW; QLD; SA

Australia; NSW; QLD; SA