News release

From:

Tiny pacemaker may enable minimally invasive transplantation

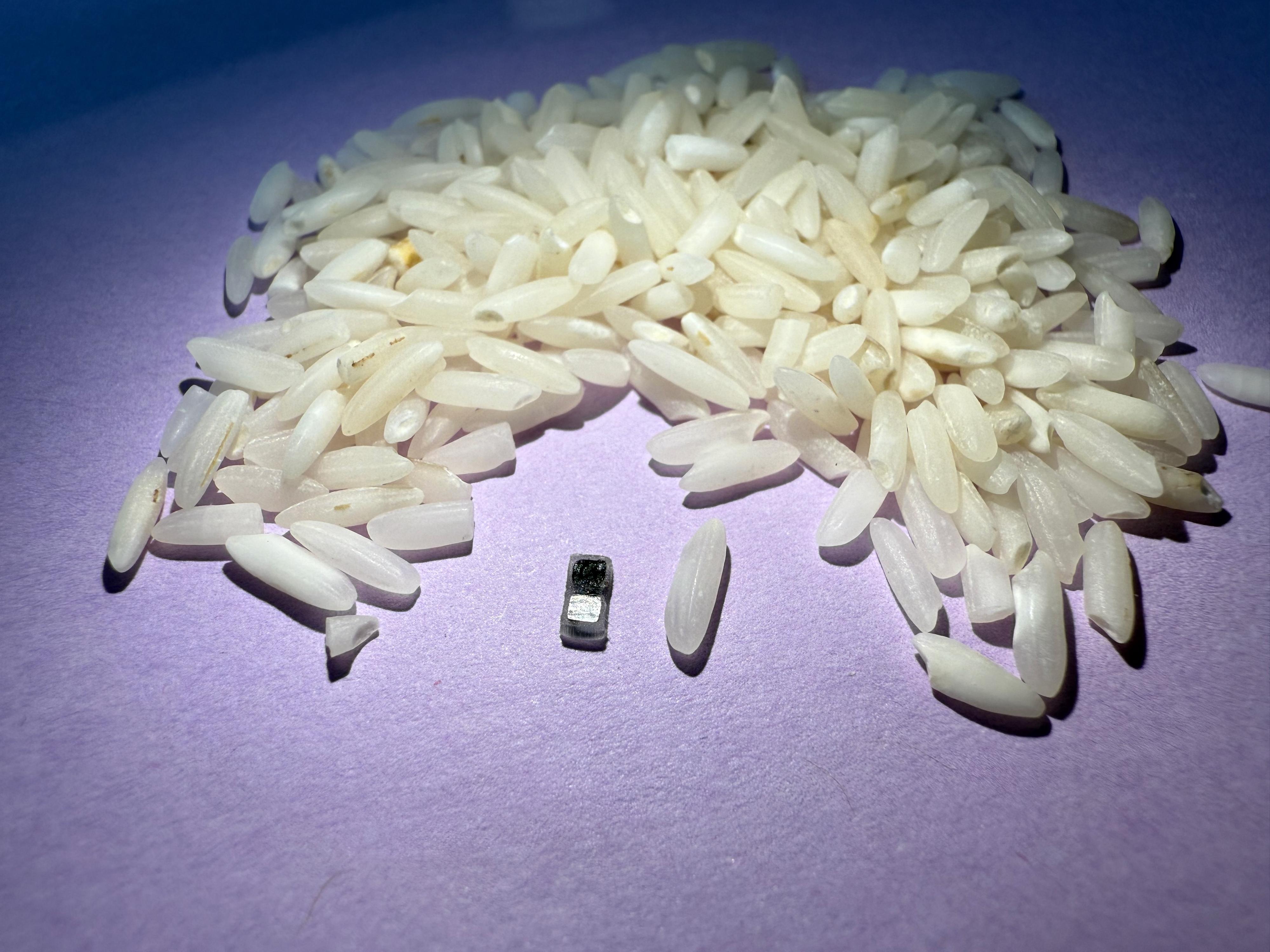

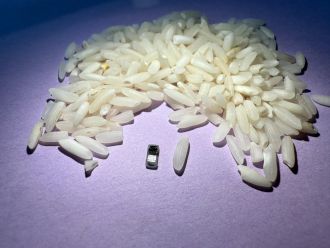

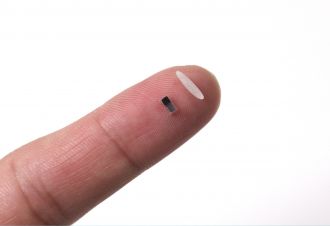

A temporary pacemaker smaller than a grain of rice capable of mediating effective cardiac pacing in animal models and human heart tissues, is presented in research published in Nature. The small, wireless device, which is eventually broken down and absorbed, could allow for minimally invasive implantation methods in patients and reduce the overall risk of treatment.

Temporary pacemakers are important for patients experiencing short-lived bradycardia (a slow heart rate) following cardiac surgery or other heart-related issues. Traditional temporary pacemakers require invasive surgeries that pose significant risks, such as infection or damage to the heart muscles, and complications from external power supplies and control systems. These challenges are greatest for young patients or those with small body sizes.

John Rogers and colleagues designed and demonstrated the effectiveness of a small temporary pacemaker in animal models and human cardiac tissues. The device measures 1.8 mm by 3.5 mm by 1 mm — smaller than any previously reported pacemaker — and can be implanted using minimally invasive techniques. The device incorporate electrodes that, when exposed to body fluids, generate an electrical current, eliminating the need for external power sources or lead wires. This setup enables the device to function autonomously when paired with a skin-interfaced wireless unit that detects cardiac activity and wirelessly controls the pacemaker using an optical method. Additionally, the device is bioresorbable (it is broken down and absorbed by the body after its useful lifetime), which eliminates the need for surgical removal after use. The authors show that the devices can control cardiac pacing in small and large animal models, such as mice and pigs, and in human hearts from organ donors.

The device may offer a potentially safer alternative to larger traditional pacemakers for temporary pacing in patients with bradycardia. Additionally, the device could potentially be adapted for other applications, such as nerve and bone regeneration, wound therapy, and pain management, the authors suggest.

Multimedia

International

International