News release

From:

WHO warns resistance to common antibiotics is increasing every year

By Steven Mew, the Australian Science Media Centre

The World Health Organization (WHO) says the rate of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) globally is outpacing advances in modern medicine, threatening the health of families worldwide.

According to the report, which uses data from the WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) from over 100 countries, one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections in people worldwide in 2023 were resistant to antibiotic treatments.

The report also found that antibiotic resistance rose in over 40% of the monitored antibiotics between 2018 and 2023, amounting to an annual increase of 5-15%.

Dr Sohinee Sarkar from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute told the AusSMC that although the report has some critical gaps in data capture, it clearly shows what the WHO have been warning about for over a decade - there has been a worrying rise in AMR in some of the most common infection types.

“As a researcher working in early-stage drug discovery of new antimicrobials, I am concerned that the GLASS report may only show the tip of the iceberg.”

“Even though countries such as Australia are doing quite well with AMR surveillance and antibiotic stewardship, this is really a global problem that requires more integration of ‘One Health/One World’ measures,” she said.

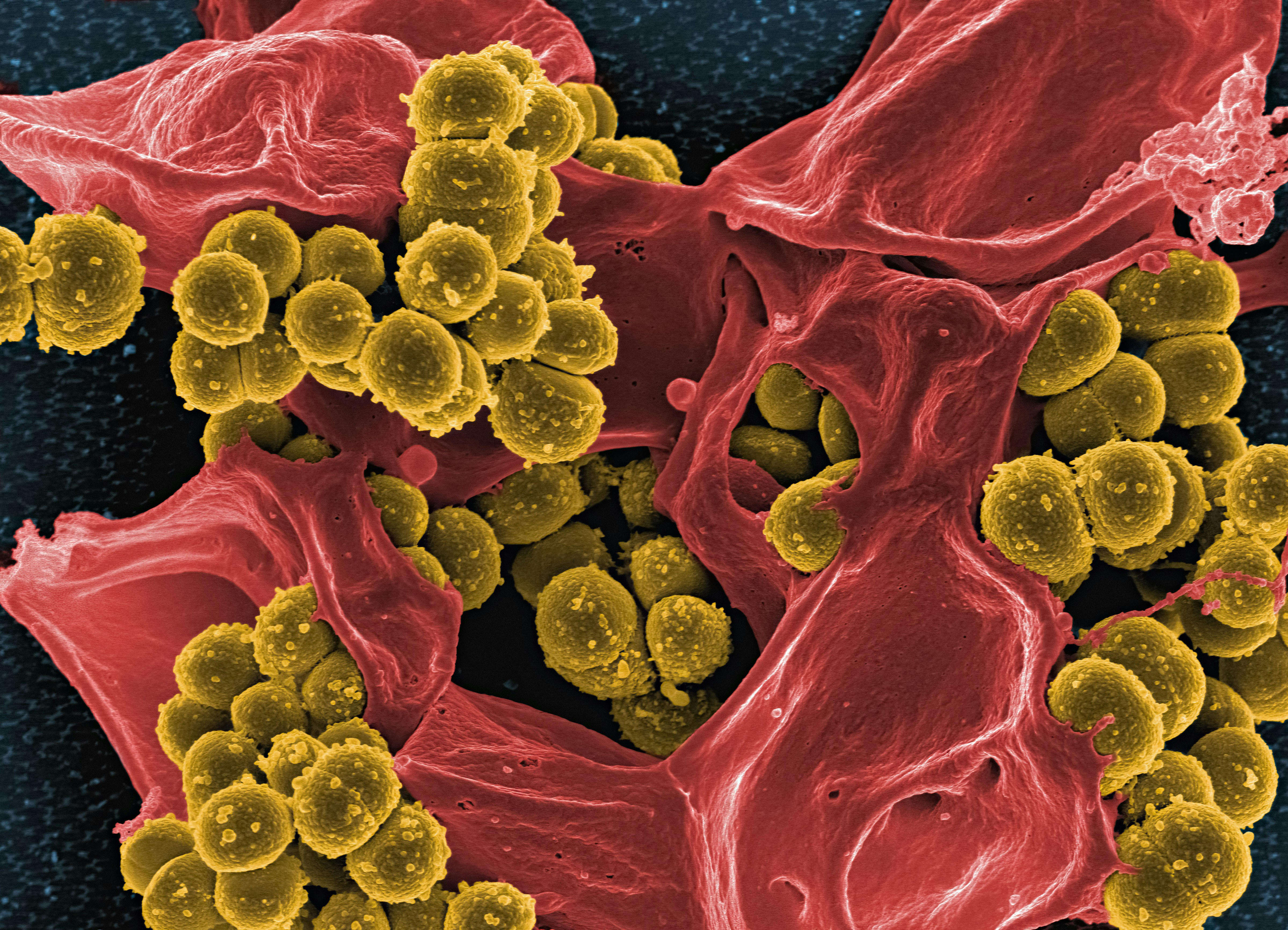

The WHO report indicates that drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are becoming more dangerous worldwide, including in Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli.

According to Associate Professor Rietie Venter from the University of South Australia, low- and middle-income countries face the greatest burden from these infections.

“These regions often struggle with limited access to newer or last-line antibiotics, exacerbating the impact of resistant infections.”

“In contrast, Australia is performing relatively well. For example, resistance to carbapenem antibiotics in A. baumannii remains below 3%, significantly lower than the global average of 54.3%,” she told the AusSMC.

However, Associate Professor Sanjaya Senanayake from the Australian National University says this shouldn’t be a source of solace for Australia.

“Studies show that antibiotic-resistant infections make it across the world through international travel, which has never been as accessible before.”

Assoc Prof Senanayake suggests that we can combat the AMR pandemic by helping poorer countries build better surveillance systems, conducting research into new vaccines, creating alternatives to antimicrobials, and increasing governmental support, among other strategies.

This article originally appeared in Science Deadline, a weekly news alert from the AusSMC. You are free to republish this story, in full, with appropriate credit.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Sohinee Sarkar is a Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Anti-Infective Research Unit at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute

Clinicians, Researchers and the World Health Organization have all been warning about the rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) for over a decade. The recent GLASS report provides an important snapshot of the current status of AMR across the world. Despite some critical gaps in data capture, the report has clearly shown the worrying rise in AMR in some of the most common infection types (urogenital, bloodstream and gastrointestinal). Specifically, AMR has increased in 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations that were monitored between 2018 and 2023.

As a researcher working in early-stage drug discovery of new antimicrobials, I am concerned that the GLASS report may only show the tip of the iceberg. Even though countries such as Australia are doing quite well with AMR surveillance and antibiotic stewardship, this is really a global problem that requires more integration of ‘One Health/One world’ measures. Some countries are relying more on the ‘Watch’ category of antibiotics (reserved for infections resistant to first line therapy) to compensate for gaps in diagnostic and surveillance capacity’. Thus, even if a new resistance pattern may emerge in one part of the world, it can easily spread to others with more robust healthcare systems.

Associate Professor Rietie Venter is the Head of Microbiology at the University of South Australia

"The recent WHO report on antimicrobial resistance, based on surveillance data from bacterial infections submitted by 104 countries, raises serious concerns. On average, one in six bacteria exhibited resistance to antibiotics. Particularly alarming are Gram-negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli, which pose significant treatment challenges. The report highlights stark regional differences, with low- and middle-income countries facing the greatest burden. These regions often struggle with limited access to newer or last-line antibiotics, exacerbating the impact of resistant infections. In contrast, Australia is performing relatively well. For example, resistance to carbapenem antibiotics in A. baumannii remains below 3%, significantly lower than the global average of 54.3%.

Overall, the findings underscore the critical importance of:

- Diagnostic tools to inform antibiotic prescription

- Antimicrobial stewardship to ensure responsible prescribing

- Robust and comprehensive surveillance systems to monitor resistance trends

To effectively implement these measures, strategies that strengthen health systems and promote equitable access to antibiotics are essential. Although not explicitly addressed in the report, supporting research and development of new antibiotics or alternative antimicrobial therapies is also vital in combating the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance."

Associate Professor Andreea Molnar is from the School of Science, Computing and Emerging Technologies at Swinburne University of Technology

"Without effective antibiotics, even routine surgeries could become dangerously risky to perform. The Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 shows a 40% increase in antibiotic resistance for the monitored antibiotics between 2018 and 2023. Approximately one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections were caused by bacteria resistant to antibiotics, with the lowest rate (one in 11) reported in the Western Pacific nations. Although this is positive news for Australia, the rate remains concerningly high, especially given the consequences of antibiotic resistance, such as loss of human lives and increased costs. Given that we live in an interconnected world, a coordinated and a multifaceted approach global effort, tailored to local contexts, is essential to effectively reduce antimicrobial resistance. On a somewhat positive note, the report highlights improvements in surveillance and monitoring, which can help provide a more accurate picture of the situation and support evidence-based decision-making in tackling the issue."

Associate Professor Sanjaya Senanayake is a specialist in Infectious Diseases and Associate Professor of Medicine at The Australian National University

"The Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025 demonstrates that antibiotic resistance remains an enormous problem globally. One positive is that 104 countries are reporting data to a global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) compared to 25 countries in 2016; yet, the completeness of data reported overall was poor (54%). But the bottom line is that between 2108 and 2023, there has been a >40% increase in antibiotic resistance with 1 in 6 infections resistant to antibiotics in 2023. Why does it matter? Because about 5 million deaths were associated with antimicrobial resistance (not just antibiotics, but also antivirals and antifungals). By 2050, this could reach 10 millions deaths a year by 2050 and have a negative impact on global GDP with global losses of USD$100 trillion.

One contributing factor to this can be attributed to antimicrobial use during the pandemic, but the reality is that antimicrobial resistance is such a complex problem. It is not just an issue of doctors prescribing antibiotics inappropriately. Instead, it also includes the vast spectrum of antimicrobial use not just in humans, but also in animals and plants, the use of the unprescribed over-the-counter antibiotics, the contamination of waterways with antibiotics, and the development of new antibiotics. Developing new antibiotics, however, is not cost-effective for businesses, so they require healthy government subsidies to make it attractive for pharmaceutical companies.

The report notes that countries with 'weaker health systems', namely poorer countries, were disproportionately affected by AMR; however, this shouldn't be a source of solace for Australia. Studies show that antibiotic-resistant infections make it across the world through international travel, which has never been as accessible before. Helping poorer countries build better surveillance systems, a One Health approach to animal/human/plant health, research into new vaccines, more rapid and cheaper diagnostics for serious infections, environmental protection of waterways, alternatives to antimicrobials, and governmental support will continue to be vital steps in the silent pandemic that is AMR."

Professor Karin Thursky is Director of the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Melbourne, and Director of the Royal Melbourne Hospital Guidance Group, as well as Associate Director of Health Services Research and Implementation Science, Director of the Centre for Health Services Research in Cancer, Deputy Head of Infectious Diseases and Implementation lead in the National Centre for Infections in Cancer at The Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

"This report is a stark reminder of the real global impact of antimicrobial resistance, but also that there are substantial gaps in data availability from those countries without the infrastructure to support effective surveillance. In Australia, we are in a fortunate situation where our rates of AMR particularly with regards to carbapenems is still very low. With regards to antimicrobial use, Australia has led the world in the surveillance of antimicrobial use appropriateness (using the National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey) and which is much more meaningful than the WHO AWARE criteria. Australian data has shown that the most highly restricted (reserve, or watch) antimicrobials are prescribed pretty well, and it is the ‘Access’ or unrestricted antimicrobials that are being prescribed poorly.

So in fact, setting targets for higher rates of Access antibiotics will not necessarily improve quality of prescribing."

Prof Mark Blaskovich is Director of Translation at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at The University of Queensland, Director of the ARC Training Centre for Environmental and Agricultural Solutions to Antimicrobial Resistance, and co-founder of the Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery

"This report, based on a global analysis of over 23 million infections confirmed to be caused by bacteria in 104 countries, found that resistance to many essential antibiotics is widespread and increasing. However, the levels of resistance are unevenly distributed, with much higher rates in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, there are large gaps in the report as many countries, particularly some that are known to have high levels of resistance, do not participate in the surveillance. Even those that do often do not have the resources to report all the necessary information. The Western Pacific Region, where Australia is grouped, had one of the lowest reported rates of resistance (9%), but notably only 10 of 27 countries in the region reported data. It is also notable that Australia’s region is situated near the South-East Asia region that has the highest levels of resistance (31%), with transmission via travel a real concern.

Particularly worrying is the finding that some of our more powerful antibiotics are being used more widely than they should be, meaning that resistance to these important antibiotics will continue to develop more quickly than it should, leading to their obsolescence. This leads to the need for new antibiotics, but as outlined in another recent WHO report, the development pipeline for new antibacterial agents is sparsely populated. While Australia is doing relatively well compared to the rest of the world, it must not be complacent and should commit to funding research that combats antibiotic resistance."

Dr Verlaine Timms is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Newcastle

"The WHO’s global report on antibiotic resistance calls for a “One Health” approach linking human, animal, and environmental health. But most of the data still comes from hospitals and clinics, focusing on human infections caused by bacteria like E. coli and Klebsiella. The findings are worrying as resistance continues to rise and treatments are failing.

But there’s a major blind spot. Antibiotic resistance isn’t limited to hospitals, and it doesn’t only spread through harmful bacteria. It can also be carried by harmless microbes found in animals, water, soil, and even within our own bodies. These microbes act as silent carriers, passing resistance genes to more dangerous bacteria. That means they play a critical role in the spread of resistance, even if they don’t cause disease themselves.

By only looking at the microbes that make people sick, we’re ignoring the bigger network that helps resistance spread. The WHO’s Tricycle survey aims to track resistant E. coli across people, animals, and the environment. But most of the data still comes from human health. To truly tackle antibiotic resistance, we need to pay attention to the microbes we usually overlook."

Dr Trent Yarwood is an infectious diseases physician and specialist with the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases

"The Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report is compiled by WHO from over 100 countries, with data on drug-resistant infections. It shows that drug resistance continues to increase around the world, but especially in areas with limited health services. Resistant infection is a major problem in Australia's part of the world - with high rates of resistance in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.

In some parts of the world, one in three infections are resistant to common antibiotics, including second- and third-line treatments. The germs that cause urine and some blood infections can be resistant to antibiotics in more than half of cases globally, and more than two-thirds in some parts of Africa. This means that simple infections - which used to be able to be treated with tablets - now need time in hospital, and in some cases have no effective treatment at all.

Everyone can do something about drug resistance - prevent infections by washing your hands, getting vaccinated and practicing good food safety. Only take antibiotics when they are necessary and only for as long as is recommended by your doctor. This report highlights that we are all connected, so the world needs to work together to help solve the problem."

Anita Williams is a Research Officer in Infectious Disease Epidemiology at The Kids Research Institute Australia

"The findings of the Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 are alarming but not surprising.

Thankfully, the proportion of resistance in Australian children is lower than global averages. In 2022-2023, we found 40% of bacteria causing bloodstream infections in Australian children were resistant to antibiotics, and 1-in-10 bacteria were multi-drug resistant – meaning they’re resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

Whilst globally 45% of E. coli were resistant to 3rd generation cephalosporins, in Australian children it was only 21.5%. For methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA), globally it was 27.1%, whilst in Australian children it was 13.6%.

However, we have observed a rise in the proportion of bacteria in children becoming increasingly resistant to first-line antibiotics. Since 2013, Enterobacterales (such as E. coli) resistant to co-trimoxazole has increased from 16.9% to 24.8%, and resistance to augmentin has increased from 4.2% to 12.8%. These antibiotics are common first-line treatment for urinary tract infections in children.

Although lower than reported globally, these numbers still represent a significant risk to paediatric healthcare in Australia. In order to protect our children, it is vital that we continue to improve surveillance efforts and fund epidemiological research into the drivers of antimicrobial resistance in Australia and beyond."

James Graham is Chief Executive Officer at Recce Pharmaceuticals Ltd

“The World Health Organization’s latest report is a stark reminder that antimicrobial resistance is rising faster than our ability to respond, and the pipeline of new antibiotics to counter this threat has all but run dry. Most antibiotic classes we rely on today were discovered between the 1940s and 1980s, and no new class has been approved in over 40 years.

This innovation gap is colliding with escalating global resistance, leaving doctors with fewer options and patients at greater risk. Infections that were once easily treated now mean longer hospital stays, higher treatment costs, and, in some cases, preventable amputations such as those seen in diabetic foot infections.

Next-generation novel approaches are urgently needed to stay ahead of this crisis.

Australia has a proud history of medical breakthroughs - Howard Florey led the team that transformed penicillin from a laboratory curiosity into the world’s first widely used antibiotic, a discovery that revolutionised medicine and saved millions of lives. Today, new technologies are emerging to rebuild the depleted antibiotic pipeline.

Recognised by WHO among antibacterial products in clinical development, these compounds offer new hope in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the defining health challenges of our time, addressing it demands innovation on a global scale.”

Australia; International; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; WA; ACT

Australia; International; NSW; VIC; QLD; SA; WA; ACT