News release

From:

Monash University researchers have uncovered why some intestinal worm infections become chronic in animal models, which could eventually lead to human vaccines and improved treatments.

Parasitic worms, also called helminths, usually infect the host by living in the gut. About a quarter of the world population is afflicted with helminth infections.

They are highly prevalent in developing countries such as sub-Saharan Africa, South America and some tropical countries in Asia. In Australia, they can be a problem in First Nations communities.

Some people can fight off the parasites due to effective immune responses. Some people who fail to develop effective immune responses suffer with a long-lasting chronic infection.

Published in Mucosal Immunology, the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute study used animal models to reveal a protective immune feature may be lacking in people who are chronically infected.

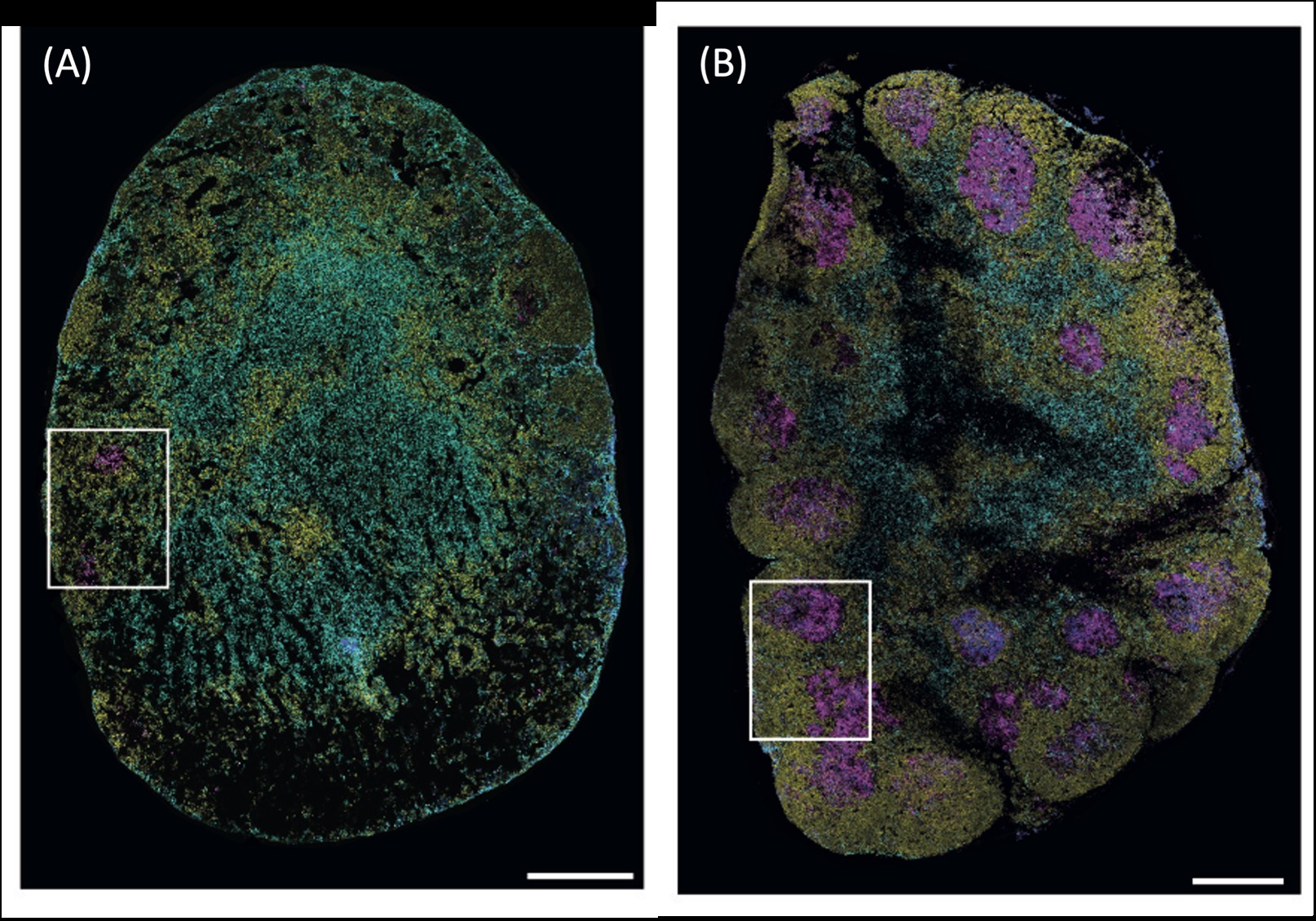

They discovered that a group of immune cells called T follicular helper (TFH) cells behaved very differently at cellular and molecular levels during acute, resolving and chronic helminth infection.

This meant that in some models the cells protected against chronic illness but in others they didn’t.

First author Dr Aidil Zaini said blocking the TFH response impaired worm clearance and promoted chronic infection, so the key was to develop ways to facilitate the protective mechanism.

He said humans also had varying immune responses, so further investigation could develop ways of protecting those prone to chronic disease.

“Our findings provide a proof-of-concept that harnessing the protective features of these immune cells may pave the way for the development of human vaccines and new drugs against helminths,” Dr Zaini explained.

“Although conventional deworming drugs can help clear the parasites, they fail to provide long-term protection and are likely to be less effective due to the development of resistance against these drugs by the parasites.”

Dr Zaini said the results were promising and warranted further investigation. He said the ultimate therapeutic goal was to develop effective vaccines against parasitic helminths in humans, which were not yet available.

“Our discovery contributes to the growing body of literature on the protective immune features during helminth infection,” Professor Zaph said.

“This knowledge can be further explored to facilitate the development of long-term immune interventions for helminth infections, as well as diseases such as allergy. Interestingly, our immune system evolves into developing a similar type of immune response during both helminth infection and allergic responses.”

Co-senior author Professor Colby Zaph said, “In addition, the fundamental discovery that TFH cells that are responding to the same infection can differ so significantly at the molecular level highlights the functional diversity that exists in our immune system, which hopefully can be exploited to manipulate immune responses in the future.”

Co-senior author Professor Kim Good-Jacobson said that parasitic worm infections continued to be a large global health burden. “Now that we can identify the tipping point between effective clearance of worms and a chronic infection taking hold, we hope this work will lead to new ways to prevent or treat these diseases," Professor Good-Jacobson said.

Read the full paper in Mucosal Immunology, Heterogeneous Tfh cell populations that develop during enteric helminth infection predict the quality of type 2 protective response

About the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute

Committed to making the discoveries that will relieve the future burden of disease, the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) at Monash University brings together more than 120 internationally-renowned research teams. Spanning seven discovery programs across Cancer, Cardiovascular Disease, Development and Stem Cells, Infection, Immunity, Metabolism, Diabetes and Obesity, and Neuroscience, Monash BDI is one of the largest biomedical research institutes in Australia. Our researchers are supported by world-class technology and infrastructure, and partner with industry, clinicians and researchers internationally to enhance lives through discovery.

Australia; VIC

Australia; VIC