News release

From:

Scientists tie obesity to sex- and age-specific genes

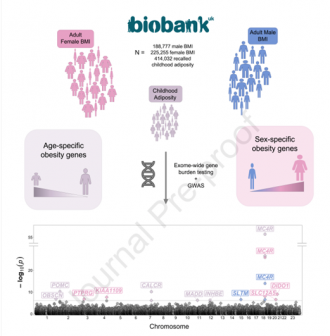

From influencing how our body stores fat to how our brain regulates appetite, hundreds of genes, along with environmental factors, collectively determine our weight and body size. Now, researchers add several genes, which appear to affect obesity risk in certain sexes and ages, to that list. The study, published on August 2 in the journal Cell Genomics, may shed light on new biological pathways that underlie obesity and highlight how sex and age contribute to health and disease.

"There are a million and one reasons why we should be thinking about sex, age, and other specific mechanisms rather than just lumping everyone together and assuming that disease mechanism works the same way for everyone,” says senior author John Perry (@jrbperry), a geneticist and professor at the Wellcome-MRC Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge, U.K. We're not expecting people to have completely different biology, but you can imagine things like hormones and physiology can contribute to specific risks.”

To untangle sex's role in obesity risk, the research team sequenced the exome—the protein-coding part of the genome—of 414,032 adults from the UK Biobank study. They looked at variants, or mutations, within genes associated with body mass index (BMI) in men and women, respectively. Based on height and weight, BMI is an estimated measurement of obesity. The search turned up five genes influencing BMI in women and two in men.

Among them, faulty variants of three genes—DIDO1, PTPRG, and SLC12A5—are linked to higher BMI in women, up to nearly 8 kg/m² more, while having no effect on men. Over 80% of the women with DIDO1 and SLC12A5 variants had obesity, as approximated by their BMI. Individuals carrying DIDO1 variants had stronger associations with higher testosterone levels and increased waist-to-hip ratio, both risk indicators for obesity-related complications like diabetes and heart disease. Others with SLC12A5 variants had higher odds of having type 2 diabetes compared with non-carriers. These findings highlight previously unexplored genes that are implicated in the development of obesity in women but not men.

Perry and his colleague then repeated their method to look for age-specific factors by searching for gene variants associated with childhood body size based on participants’ recollections. They identified two genes, OBSCN and MADD, that were not previously linked to childhood body size and fat. While carriers of OBSCN variants had higher odds of having higher weight as a child, MADD variant carriers were associated with smaller body sizes. In addition, the genetic variants acting on MADD had no association with adult obesity risk, highlighting age-specific effects on body size.

"What's quite surprising is that if you look at the function of some of these genes that we identified, several are clearly involved in DNA damage response and cell death,” says Perry. Obesity is a brain-related disorder, whereas biological and environmental factors act to influence appetite. "There's currently no well-understood biological paradigm for how DNA damage response would influence body size. These findings have given us a signpost to suggest variation in this important biological process may play a role in the etiology of obesity.”

Next, the research team hopes to replicate the study in a larger and more diverse population. They also plan to study the genes in animals to peer into their function and relationship with obesity.

"We're at the very earliest stages of identifying interesting biology,” says Perry. "We hope the study can reveal new biological pathways that may one day pave the way to new drug discovery for obesity."

Multimedia

International

International