News release

From:

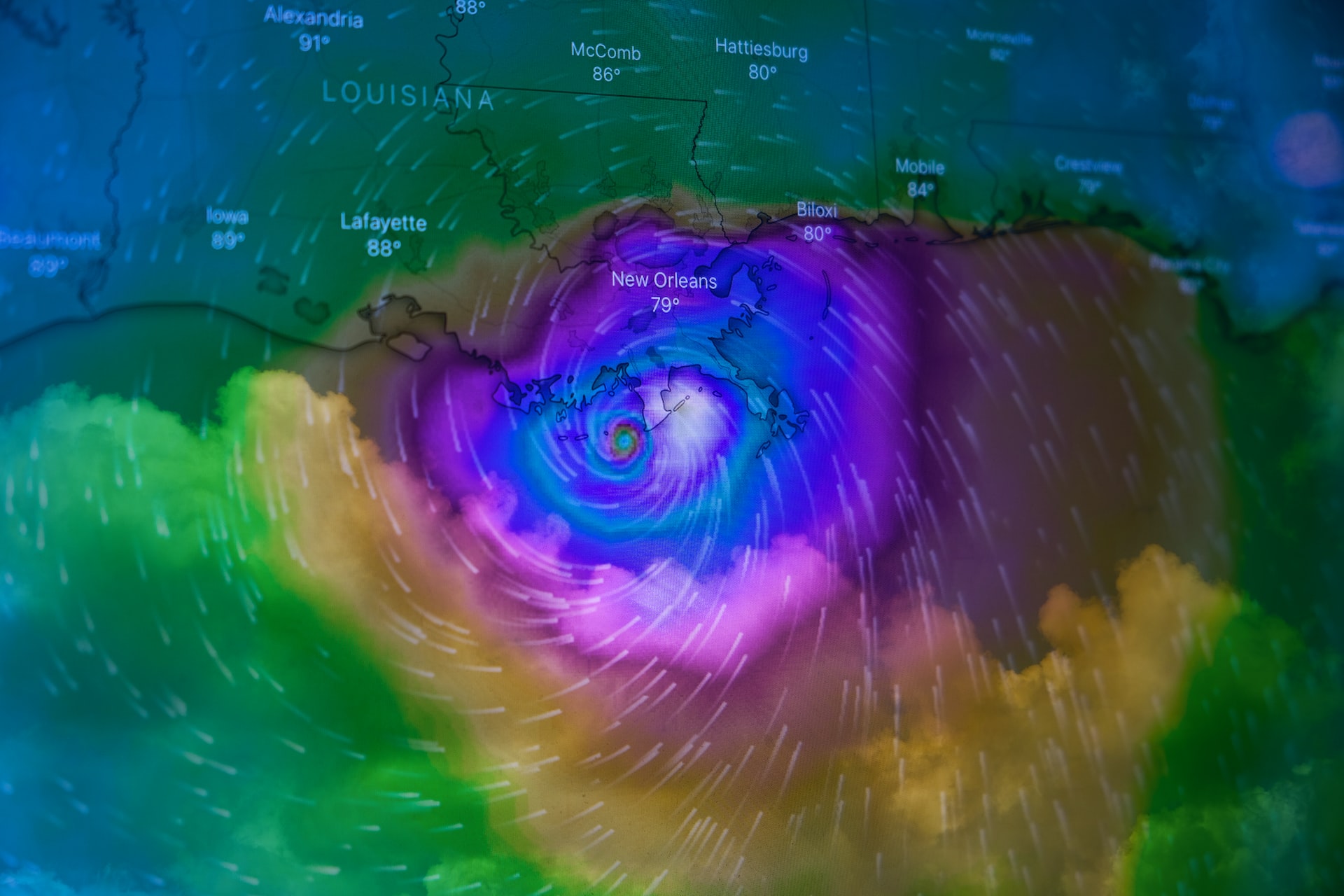

Climate change could increase the likelihood of two tropical cyclones impacting the same coastal region within 15 days across the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts by the end of the century, according to a modelling study published in Nature Climate Change.

Tropical cyclones are one of the most devastating natural hazards for coastal areas, causing damage through strong winds, heavy rainfall and storm surges. How climate change affects these features of storms is complex. Most studies focus on the impact of climate change on single storms, while the risk of compound events — an event where two tropical cyclones impact the same location within a short time period — is not well understood. These events can be particularly damaging, as buildings and infrastructure will be more vulnerable to further damage, which also puts the lives of affected populations at risk.

Ning Lin and colleagues used climate models to assess how the frequency of successive tropical cyclone impacts (within 15 days of each other) changes along the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts under different emissions scenarios. Currently, successive hurricanes can affect coastal regions once in every 10 to 92 years, depending on the location. The authors find that under a moderate-emissions scenario (where CO2 emissions start to fall after 2050 but do not reach net zero by 2100), this average drops to 1 to 3 years, and under a high-emissions scenario (where CO2 emissions double by 2050), which is generally considered unlikely, it becomes 1 to 2 years by the end of the century. This change is linked to a higher tropical cyclone landfall frequency, as well as sea-level rise and increased storm intensity.

The authors note that there are uncertainties about the climate warming impact on the frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones, but conclude that their findings indicate that coastal resilience and infrastructure planning needs to consider an increased risk from sequential tropical cyclones during the twenty-first century.

Expert Reaction

These comments have been collated by the Science Media Centre to provide a variety of expert perspectives on this issue. Feel free to use these quotes in your stories. Views expressed are the personal opinions of the experts named. They do not represent the views of the SMC or any other organisation unless specifically stated.

Dr Dáithí Stone, climate scientist, NIWA, comments:

What the authors of this study find is that the potential for damage from two tropical cyclones (hurricanes) affecting the United States one after the other will be much higher in the future because their winds will be more intense, they will dump more rain, and because sea level will be higher (affecting the amount of coastal flooding). These are changes that are widely expected under human-induced climate change. The authors also conclude that tropical cyclones will be more frequent, and so more likely to follow closely one after another, but the evidence that this will happen in a warmer world is at best shaky. For the most part, they are pointing out that if we expect the damage from any individual tropical cyclone in the future to be, say, double what it is now, then the damage from two sequential tropical cyclones might be 2*2=4 times as much as from two sequential tropical cyclones now.

I am not sure the logic works the same way in Aotearoa New Zealand. Here, tropical cyclones are rare, requiring unusual winds (with a strong 'blocking high' to our east) to send them our way. But when these winds happen they can linger, so we seem to sometimes have tropical cyclones (or their remnants) arriving in close succession, for instance with Cook and the remnants of Debbie in 2017. So for us the question of whether we might see more potential for damage from sequential tropical cyclones is closely tied to how those blocking highs might change in the future; that is a hard one to figure out.

But we do have plenty of types of weather systems in New Zealand in addition to tropical cyclones that are capable of delivering damaging rain, like 'atmospheric rivers' and the sort of local convective system that hit Auckland a couple of weeks ago. Like with tropical cyclones, when these weather systems will occur in a future warmer world, we expect them to be holding more moisture and so to dump more rain. So if we were to have two sequentially in the future, then the "2*2=4" logic above would hold. And yes, this is what the northern half of the North Island has experienced this summer, a number of atmospheric rivers, that big short dump in the case of Auckland, and then Gabrielle.

So this research applies to New Zealand in the general sense of what will happen with sequential rain-dumping storms, but it is not clear that it also applies to sequential tropical cyclones.

International

International