News release

From:

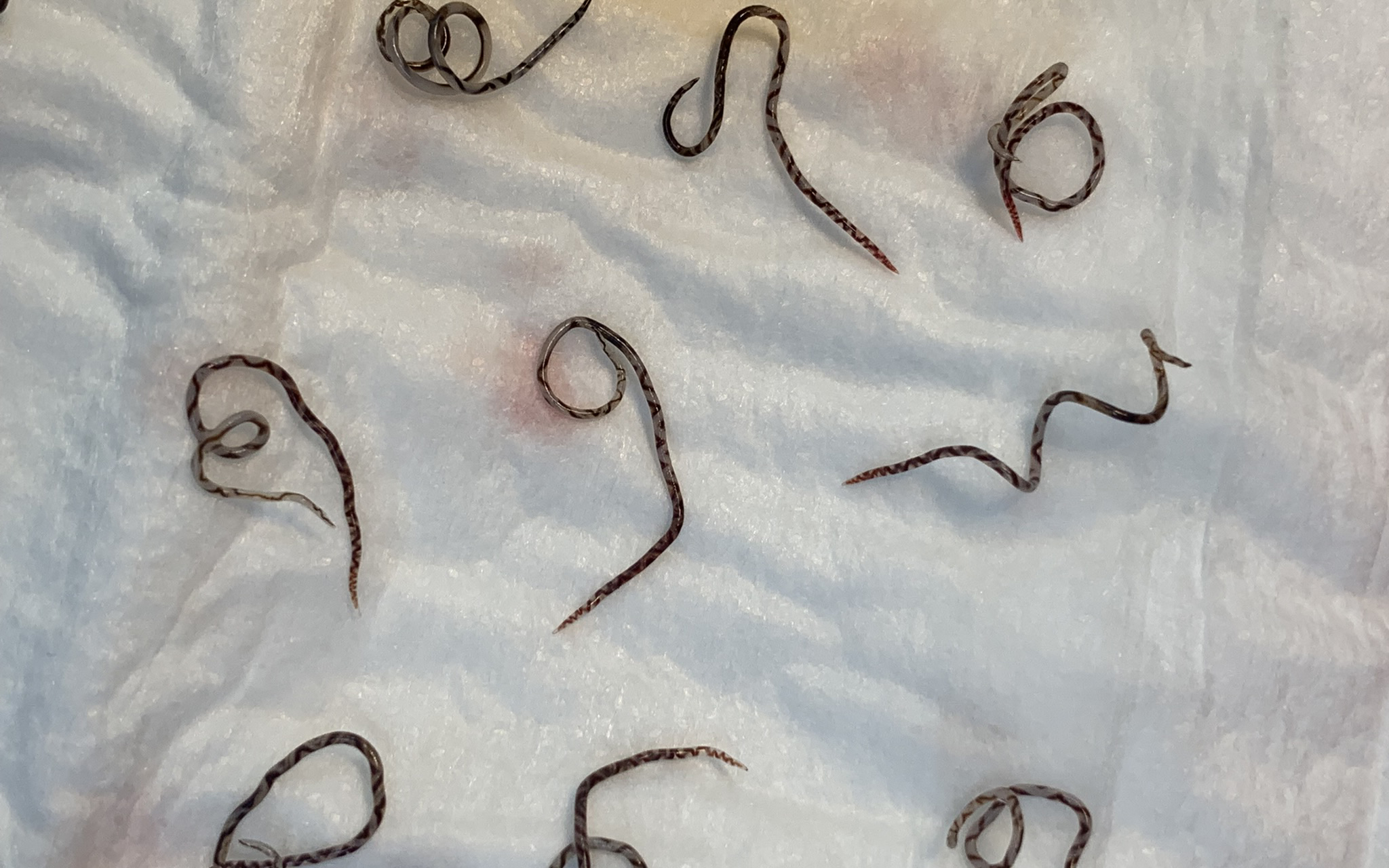

Rat lungworm disease is on the rise in eastern Australia in dogs – and there have even been recorded cases in humans, including two known lethal incidents. Caused by a parasite naturally found in rats, the disease requires ongoing monitoring to ensure it is controlled and doesn’t pose a public health threat.

Research by veterinary scientists at the University of Sydney has unveiled insights into what is behind the growth in the disease, also known as neural angiostrongyliasis. Their study highlights how climatic factors act as drivers for this potential public health issue.

They publish their findings in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

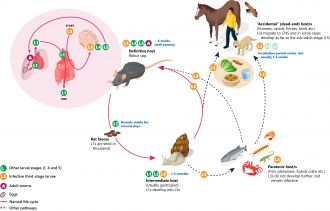

Rat lungworm disease has spread from its origins in Southeast Asia to regions including Australia, North America and Europe. Naturally found in feral rats scavenging in our cities, the parasite causing the disease is transmitted through snails and slugs, which act as intermediary hosts.

Senior author Professor Jan Šlapeta from the Sydney School of Veterinary Science said: “These snails and slugs, and the infective worm larvae in them, can – accidentally – be a disease source to us humans and our pet dogs. Once in humans or dogs the worms quickly get to brain where they cause disease.”

Professor Šlapeta and his team analysed five years of data to develop a model that identifies high risk periods for transmission of the disease between two- and 10-months after heavy rainfall. The scientists identified 93 cases in dogs in the study period, with a peak of 32 in 2022. This peak was due to high rainfall, a driver of snail and slug proliferation.

Professor Slapeta said: “This is another example how the La Niña events with wetter than average periods in Australia lead to increased disease transmission and occurrence.”

The confirmed cases in the study were in and around Sydney and Brisbane, likely due to access to emergency veterinary care and higher population density.

The results shed light on the intricate relationship between climatic and weather conditions, such as rainfall and temperature fluctuations, and the threat of emergence of the disease in humans and domestic dogs.

Rat lungworm disease is caused by the parasite Angiostrongylus cantonensis, which is naturally found in rats. However, humans and dogs are considered accidental hosts, and infection can lead to devastating neurological consequences.

Lead author Phoebe Rivory, who has submitted her PhD thesis to the Sydney School of Veterinary Science, said: “In dogs and humans, the parasite enters the brain but rather than progressing to the lungs like it does in rats, it is killed in the brain by our own immune response. It is that overt immune response that causes severe headaches and sensations.”

Using a One Health approach, which emphasises the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health, the researchers examined a dataset of canine infections to inform potential risks for human populations. By monitoring canine neural angiostrongyliasis cases, the team aimed to fill a significant gap in understanding how climate factors drive the occurrence of this zoonotic disease, an infection that jumps from animals to humans.

Notably, this research emphasises the importance of identifying the high-risk periods for transmission, allowing for targeted public health interventions to mitigate the spread of the disease. The study found that climatic patterns influenced the seasonal occurrence of rat lungworm disease, increasing the likelihood of transmission to dogs and potentially to humans.

Professor Šlapeta said: “This work is a clear representation of the One Health approach, illustrating how insights gained from studying animal diseases can effectively inform human medicine. With ongoing changes in climate, understanding the epidemiology of rat lungworm disease becomes imperative for protecting our pets and ourselves.”

The implications of this research are particularly poignant, especially when recalling the tragic case of Sam Ballard, who died seven years ago after consuming an infected slug in 2010. There have been at least half a dozen recorded cases in humans since the 1970s in Australia, including at least one other fatal incident.

These underscore the potential severity of rat lungworm disease, reinforcing the urgent need for heightened awareness and preventive measures.

As the number of reported cases in dogs rises, this study serves as a call to action for health professionals, policymakers and the public to remain vigilant.

Professor Slapeta said: “Educating communities about how to avoid infection – by steering clear of potentially infected slugs and snails – can be lifesaving. And programs to inform dog owners on what symptoms to look out for in their pets would be worthwhile.”

The research team encourages further investigation into the impact of environmental changes on disease dynamics. This would be assisted by including data on snail and slug abundance and the related availability of infective parasite larvae.

## ENDS ##

Download photos of the researchers and worms and a video of the lungworms at this link.

View and embed the video short on YouTube at this link.

Research

Rivory, P. et al ‘Rainfall and temperature driven emergence of neural angiostrongyliasis in eastern Australia’ (The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2025) DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiaf173

Declaration

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The study was in part funded by the Betty & Keith Cook Canine Research Fund at the Sydney School of Veterinary Sciences at the University of Sydney.

Multimedia

Australia; NSW; QLD

Australia; NSW; QLD