News release

From:

Zoology: Big birds are not always bird-brained

Emus and rheas may be capable of problem solving, suggests research on a captive population of nine birds published in Scientific Reports. The findings indicate that both species demonstrated multiple problem-solving approaches to a cognition puzzle through individual trial and error learning, showing an ability to innovate previously not associated with palaeognaths, an evolutionary branch of birds.

Palaeognathae is a small group of birds which includes several species that have evolved flightlessness and gigantism, such as emus, ostriches, and the now-extinct giant moa. Little is known about the cognitive abilities of palaeognaths, which have smaller relative brain sizes compared to other birds, as most research into bird cognition has focused on the problem-solving abilities of larger-brained species such as crows or parrots.

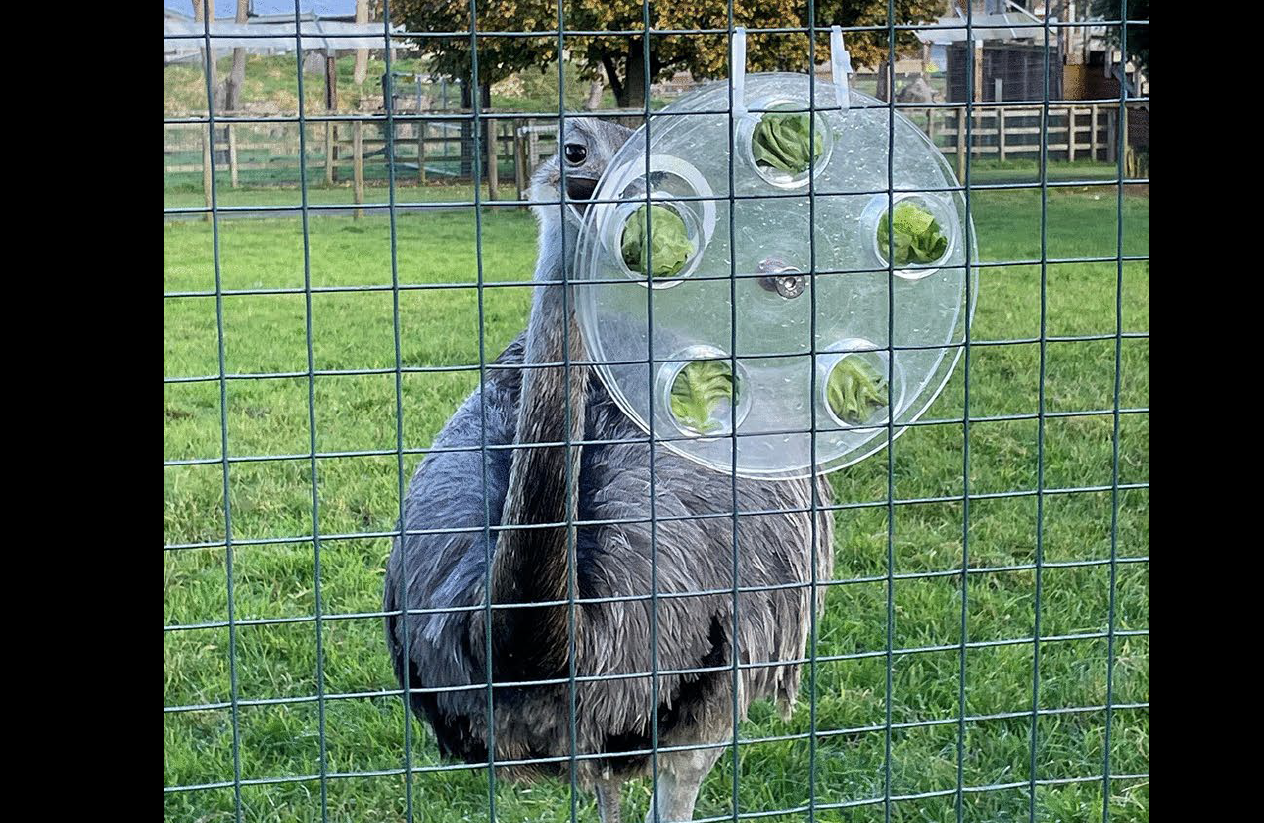

Fay Clark and colleagues designed a puzzle to test the problem-solving abilities of several zoo palaeognaths — three emus, two rheas, and four ostriches. The puzzle required the birds to line up holes in a plastic wheel held together by a nut and bolt to obtain a food reward. Each bird species was first shown a solved version of the puzzle with the food freely available, then given an unsolved puzzle to complete within 30 minutes. All three emus solved the puzzle on the first attempt and could solve it again once the puzzle was reset; one rhea obtained the reward without correctly solving the puzzle by dismantling it, loosening the bolt from the nut to uncover all five food chambers. However, on subsequent attempts the rhea solved the puzzle by spinning the wheel as intended. None of the ostriches were able to solve the task.

The authors note that some of the limitations of the study include the relatively simple puzzle design, and that larger-brained crows would likely have been able to solve the puzzle. The authors suggest that ostriches likely underperformed on account of their smaller relative brain size. As the behaviour of palaeognaths has been proposed as similar to some dinosaurs, Clark and co-authors also suggest that the ability to innovate may have evolved earlier than previously thought.

Multimedia

Australia; International

Australia; International