News release

From:

Stanford Medicine study flags unexpected cells in lung as suspected source of severe COVID

The lung-cell type that’s most susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is not the one previously assumed to be most vulnerable. What’s more, the virus enters this susceptible cell via an unexpected route. The medical consequences may be significant.

Stanford Medicine investigators have implicated a type of immune cell known as an interstitial macrophage in the critical transition from a merely bothersome COVID-19 case to a potentially deadly one. Interstitial macrophages are situated deep in the lungs, ordinarily protecting that precious organ by, among other things, engorging viruses, bacteria, fungi and dust particles that make their way down our airways. But it’s these very cells, the researchers have shown in a study to be published online April 10 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, that of all known types of cells composing lung tissue are most susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2.

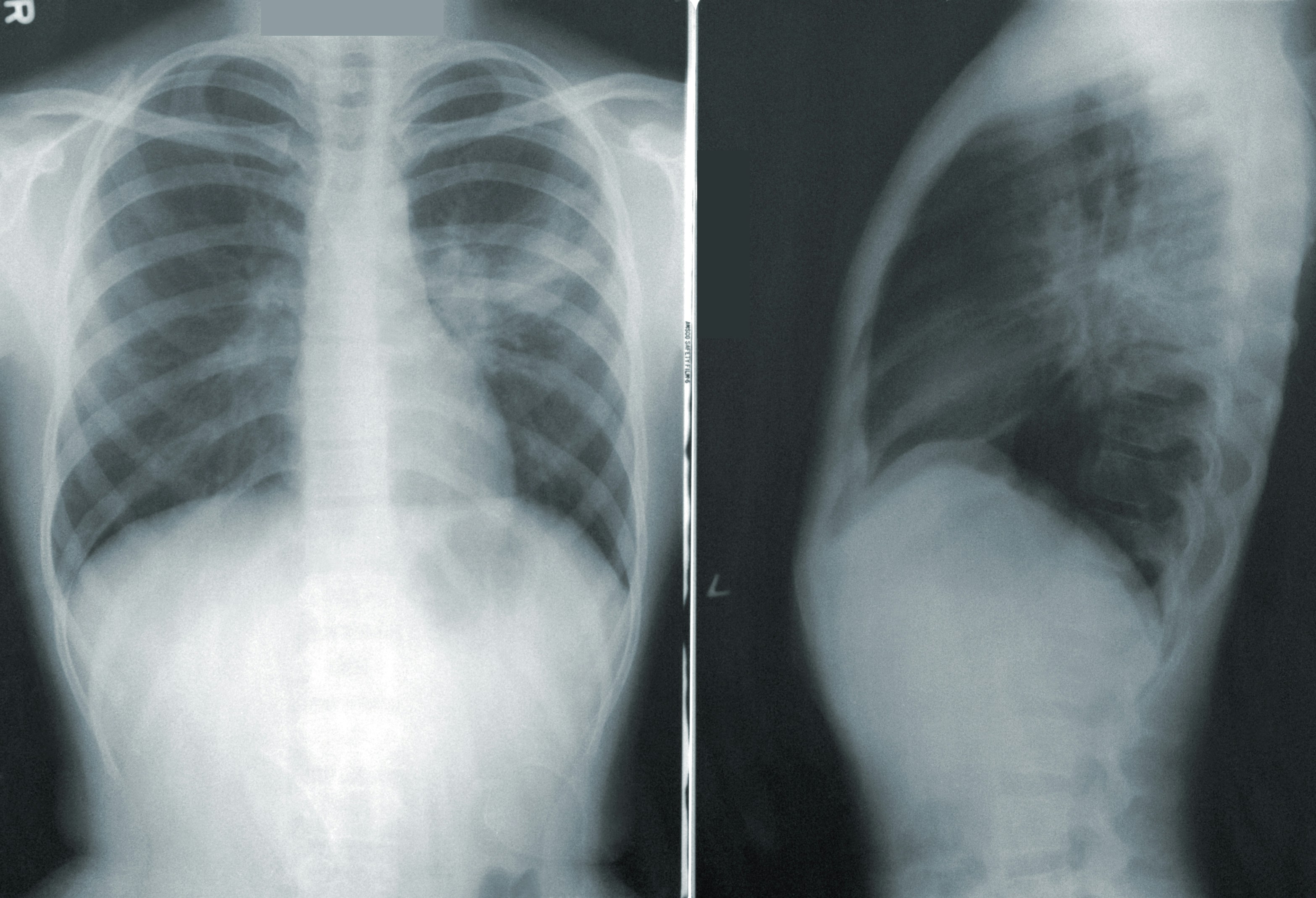

SARS-CoV-2-infected interstitial macrophages, the scientists have learned, morph into virus producers and squirt out inflammatory and scar-tissue-inducing chemical signals, potentially paving the road to pneumonia and damaging the lungs to the point where the virus, along with those potent secreted substances, can break out of the lungs and wreak havoc throughout the body.

The surprising findings point to new approaches in preventing a SARS-CoV-2 infection from becoming a life-threatening disease. Indeed, they may explain why monoclonal antibodies meant to combat severe COVID didn’t work well, if at all — and when they did work, it was only when they were administered early in the course of infection, when the virus was infecting cells in the upper airways leading to the lungs but hadn’t yet ensconced itself in lung tissue.

“We’ve overturned a number of false assumptions about how the virus actually replicates in the human lung,” said Catherine Blish, MD, PhD, a professor of infectious diseases and of microbiology and immunology and the George E. and Lucy Becker Professor in Medicine and associate dean for basic and translational research.

Blish is the co-senior author of the study, along with Mark Krasnow, MD, PhD, the Paul and Mildred Berg Professor of biochemistry and the Executive Director of the Vera Moulton Wall Center for pulmonary vascular disease.

“The critical step, we think, is when the virus infects interstitial macrophages, triggering a massive inflammatory reaction that can flood the lungs and spread infection and inflammation to other organs,” Krasnow said. Blocking that step, he said, could prove to be a major therapeutic advance. But there’s a plot twist: The virus has an unusual way of getting inside these cells — a route drug developers have not yet learned how to block effectively — necessitating a new focus on that alternative mechanism, he added.

International

International